Arabesque

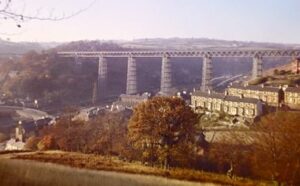

I was born in South Wales, in the small coal mining town of Crumlin, in a small cottage called Cil-y-Coed. Set a little apart from the town, it overlooked the Ebbw Valley, which was bisected by a large viaduct whose chief fame, aside from being the tallest in Britain, was that it featured in a film, Arabesque, starring Sophia Loren and Gregory Peck.

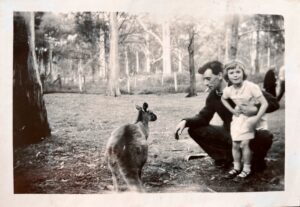

When I was four we emigrated to Australia in pursuit of a better life, accompanied by my widowed maternal grandfather, a school-teacher, who I adored and who taught me to read and engendered in me a life-long love of books.

We crossed the Equator on the voyage out, the occasion marked by a ceremony presided over by Neptune. It was a scene I did my best to recreate in my novel, Flock, though I suspect I managed to no more than hint at the true terror of that day, the adults suddenly all gone mad, tossing people willynilly into the water, streaked with what looked like vomit, and overall the gut-clenching smell of brine.

![]()

We’d barely set foot in Australia before my mother professed herself homesick. We managed three years, first in Melbourne, then across the Nullabor to Perth, before returning to Wales, to a winter so brutal I suspect even my mother must have harboured a few regrets.

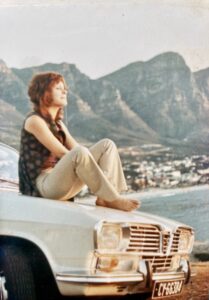

Five years later we again moved, this time to South Africa, my father having been offered a white-collar job in a factory near Cape Town. In a small white hotel by the sea, I fell asleep those first weeks to the sound of breaking waves, believing myself in paradise. Only for paradise to be rudely exchanged for Blomtuin (flower garden), an ill-named, sun-scorched, leafless new satellite suburb of Bellville, 30km inland on the edge of the Cape Flats. Summer-long the south-easter threw up sheets of sand and loose detritus and wherever you looked were tin shanties and factories and poverty and oppression. By chance, we ended up living next door to Bellville’s Afrikaans mayor and though my mother, always prone to favouring the personal over the political, complained bitterly of his treatment of their cat, she and I were often to be found peering out from behind the curtains at the sleek black car come to spirit him away to his mayoral duties.

At sixteen I left school, Settler’s High, rebellious and determined to make my own way in life. I enrolled at the Terblanche Secretarial College, in Cape Town, only within weeks to find myself breaking the law by falling hopelessly in love with a young man of colour, a musician, who would later go partway to inform the character of Lennie Naidoo in The Bright House. We lived some months in a squat in Cape Town where the neighbours would almost daily throw garbage over the wall at us as if to signal their contempt, or so we presumed, for any white person who would willingly choose to live in abject poverty. Unsurprisingly, the love affair was doomed.

Heart-broken, I returned to my parents’ home and went to work as a copy typist, in a Bellville factory. Only a thin particle-board wall separated the stifled confines of the secretarial pool from the factory floor and the spaghetti canning line, a world I quickly grew to envy. Raucous, full of life, split by shouts of rage, peals of laughter, it was a world composed almost entirely of women, and one which I attempted to pay homage to in The Factory.

By nineteen, I was married, to an Australian, a young supervisor at the factory and two years later gave birth to a son, Jesse and, four years after that, to a daughter, Shelley. I was on the cusp of turning thirty when I found myself emigrating with my family to Australia for the second time. Steve Biko had died in custody at the hands of the police a few years before, an end-point which had led to something of a minor exodus of white liberals. It was also the year I found myself increasingly at odds with myself, yearning for something that I couldn’t even begin to formulate, never mind articulate.

It finally found expression in a creative writing course at the Willoughby Arts Centre. Though the end result, my falling in love with the teacher, the late poet Dorothy Porter, and she with me, certainly hadn’t figured in anyone’s concept of my destiny. Once the considerable dust had settled, Dorothy and I moved to the Blue Mountains, to a small fibro cottage in Mount Victoria, where I wrote my first short story, The Plain Clothes Man, published by Bruce Pascoe in Australian Short Stories. When Bruce asked for more, I began a collection of what I told myself were linked short stories but which soon found a life of its own in the form of The Factory.

I had almost finished work on my second novel, One Way Mirrors, set in the white middle-class suburbs of Johannesburg, a milieu I knew only too well, when what I thought was an enduring relationship came to an abrupt and painful end. Not that the love ceased, but the fidelity.

Licking my not inconsiderable wounds, I met my present partner, Sarah, in a perfect match of opposites, the year I turned forty, at a dinner party hosted by the then literary editor of Sydney Morning Herald. A chance encounter that seemed to augur well for the future, more than borne out after almost thirty years of a shared life overflowing with novels-in-progress, arts and animals, good food and friends, travel and gardens, house renovations, children and grandchildren, the latter now living in close proximity. Settled once more in a small close-knit community, surrounded by family, one might ask whether I have come full circle. All I can say with any certainty is that I have come far, far further than I ever dreamed of. And that rather than a circle, my life owes far more to the arabesque, that exquisite pattern of lines that briefly intertwine only to once more flow on.

June 2022